Latest posts

A masterclass in creating value

What’s going on at parkrun?

Virtue-signalling all the way to the bank

Bud Light: brand purpose or virtue-signalling?

The Coddling of the American Mind, by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt

Belonging, by Owen Eastwood

Such a simple thing

The Long Win, and The Scout Mindset

The Cult of We by Eliot Brown and Maureen Farrell

Coffee and covid modelling

By theme

Marketing strategy

Insight & metrics

Innovation & inspiration

Brand & positioning

Marketing communications

Business purpose

Leadership

By industry sector

Financial services

Retail

FMCG

Technology & start-ups

Consumer services

Business to business

Other sectors

By type

Books

Comment

Quotes

Thought leadership

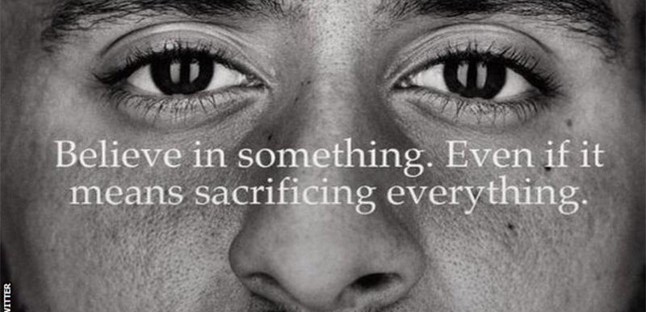

If all publicity is good publicity, then Nike’s recent ad featuring Colin Kaepernick is a triumph. Widespread reports of outraged Americans burning Nikes is just free media coverage – reportedly $43m worth in 24 hours. Or, you may believe most people aren’t much interested in what brands do, the shoe-burners aren’t valuable customers, and anyway our memories for controversy are short. So, like the VW emissions scandal, or British Airways misleading Virgin Atlantic passengers, it will soon be forgotten.

On the other hand, the share price fell on the news of anti-Nike protests, and brand tracking data has shown a dramatic drop-off in brand regard, among brand buyers and non-buyers alike, and across the political divide. Even people who support the Take A Knee protest think less positively of Nike now, though their view may change, and their behaviour may not.

Both these positions are about whether the decision Nike took – to get involved with a controversial, arguably political, issue and figure – is good or bad for business. What puzzles me is why people at Nike thought this had anything to do with their brand and needed a response in their advertising. Whether it’s naïve to think your consumers must share your political beliefs, or self-important to think brands should use their reach and clout for whatever their version of good is, or cynical to piggyback for profit on someone else’s principled stand, which cost him money, it’s a long way from “Just do it”. Given they are about sport it’s not surprising that taking a knee was talked about in Portland. But why make it a consumer issue?

Nike is about participation. Wearing Nike helps me feel I can perform and compete. Nike-sponsored athletes embody this attitude, and the achievement it can bring. I can’t see that the brand needed to adopt a position on TAK. There are social issues on which brands have to be clear. If you buy Nike, you are in effect endorsing its sourcing practices, so you may want reassurance that it doesn’t use sweatshops or child labour. The company is also defending lawsuits alleging horribly sexist practices in its US offices. But now they’re making me take a stand (knee) on US civil rights. Even people who agree with the take a knee campaign may want their leisure choices to be apolitical.

Levi Strauss has recently announced donations to, and participation in, gun control campaigns in the USA. This is no closer to its core business than civil rights for Nike, but at least it’s a corporate move, in that it’s their behaviour as a business that’s changing, not their marketing messaging. One wonders what behaviour from Nike would legitimise its use of Colin Kaepernick in its advertising. A demonstrable commitment to equality of employment opportunities and practices, perhaps?

Those cynical that Nike has suddenly found a social conscience say this is a hard-nosed commercial decision which indicates Nike’s confidence that non-racists are in the majority – or at least spend more on “athleisure”. But which side of the political divide is commercially best for brands like these isn’t the point. It’s whether marketers are getting it wrong in embracing every social and political issue out there, instead of focusing on, and fixing, the ones that connect to their business, on which their customers need to know where they stand.

Latest posts

A masterclass in creating value

What’s going on at parkrun?

Virtue-signalling all the way to the bank

Bud Light: brand purpose or virtue-signalling?

The Coddling of the American Mind, by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt

Belonging, by Owen Eastwood

Such a simple thing

The Long Win, and The Scout Mindset

The Cult of We by Eliot Brown and Maureen Farrell

Coffee and covid modelling

By theme

Marketing strategy

Insight & metrics

Innovation & inspiration

Brand & positioning

Marketing communications

Business purpose

Leadership

By industry sector

Financial services

Retail

FMCG

Technology & start-ups

Consumer services

Business to business

Other sectors

By type

Books

Comment

Quotes

Thought leadership